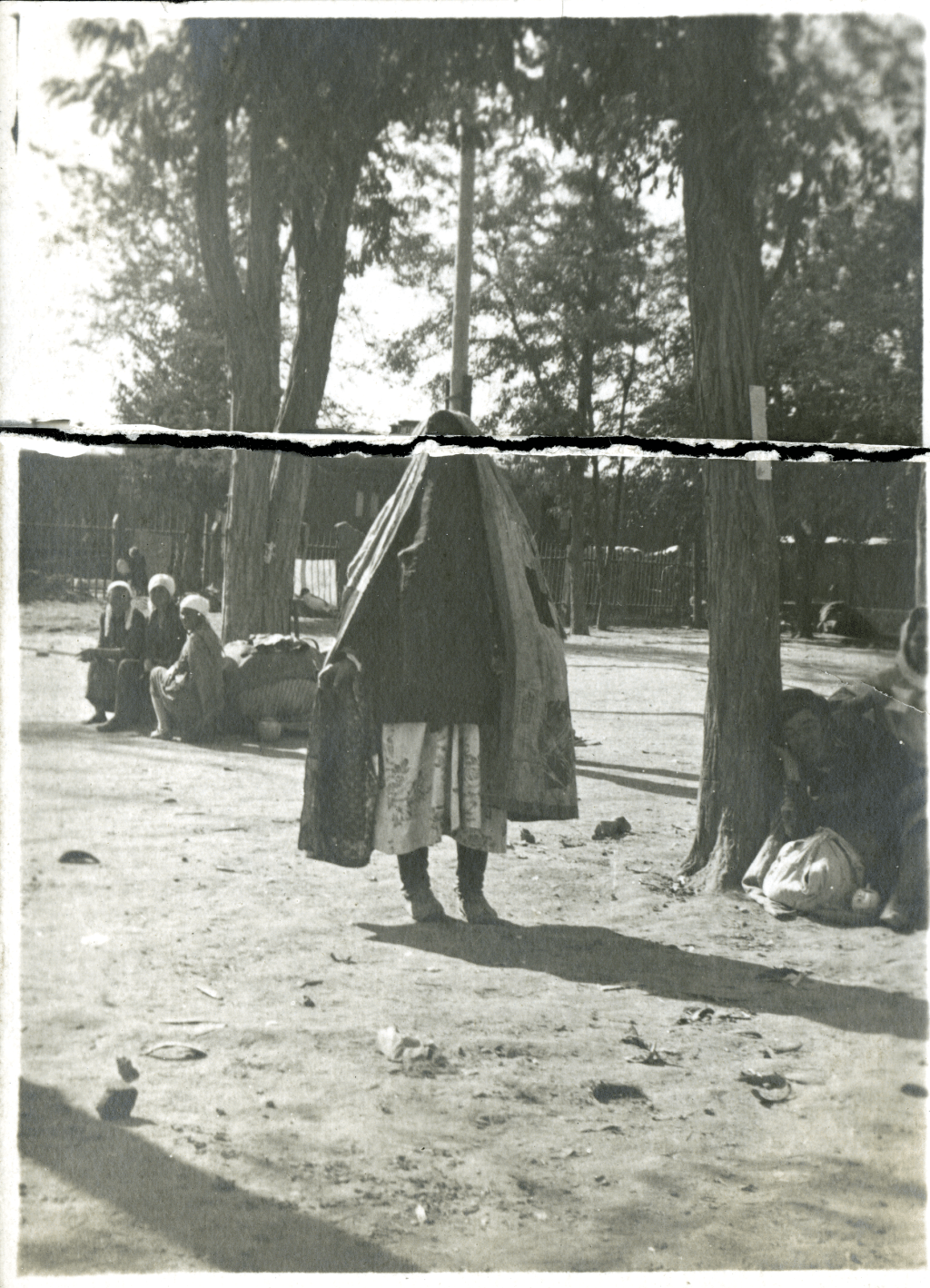

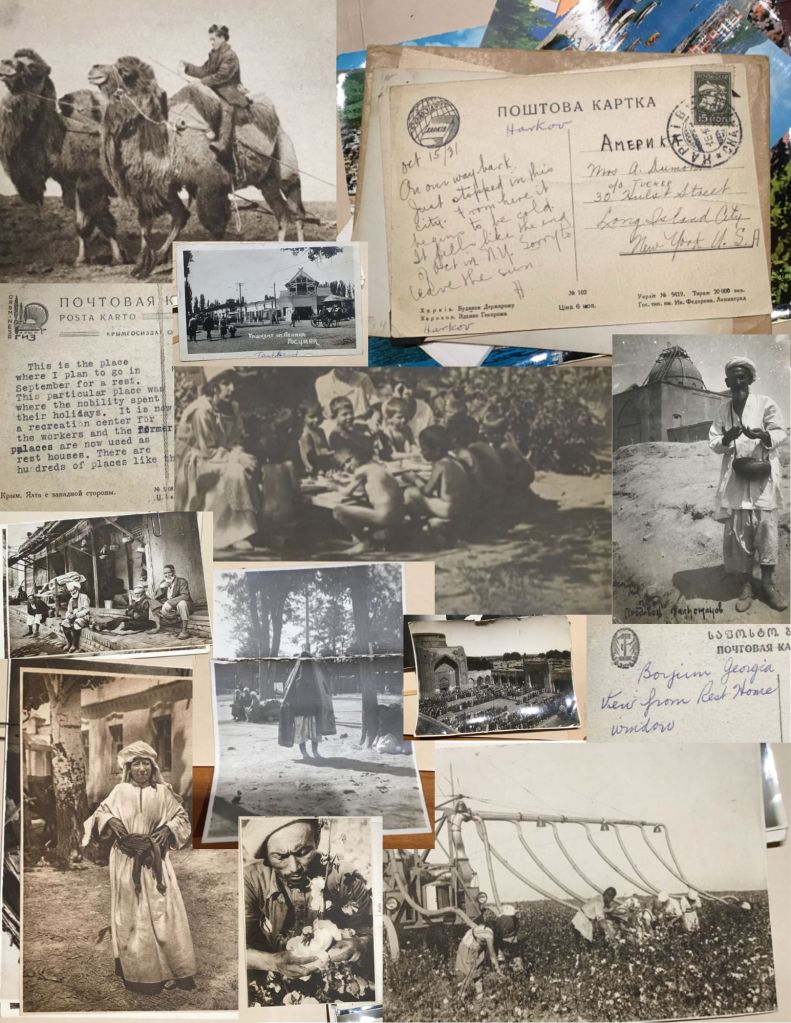

In the Tamiment Library at NYU, among the folders and boxes of Hermina Dumont Huiswoud Papers,” lies a postcard that seems, at first glance, unremarkable: a small photographic print depicting a veiled woman* – the asterisk I add to trouble gendered assumptions – somewhere in Soviet Central Asia.1 The image is fractured – creased through the middle, its paper brittle with time, its edges faintly discolored. No message graces the back. There’s no date, no signature, no record of where Hermina Dumont Huiswoud got it.

And yet this fragile, almost accidental object has become a key to reimagining one of the most intriguing figures of Black radical Internationalism in the early twentieth century – a woman who moved through Harlem, Moscow, and the Caribbean; who crossed borders both political and personal; and who left behind not a self-narrative, but fragments, letters, and the stories of others.

The damaged postcard – this silent witness to unfulfilled connections – invites us to think about what it means to build solidarity across difference, empire, and time.

A Life Told Through Others

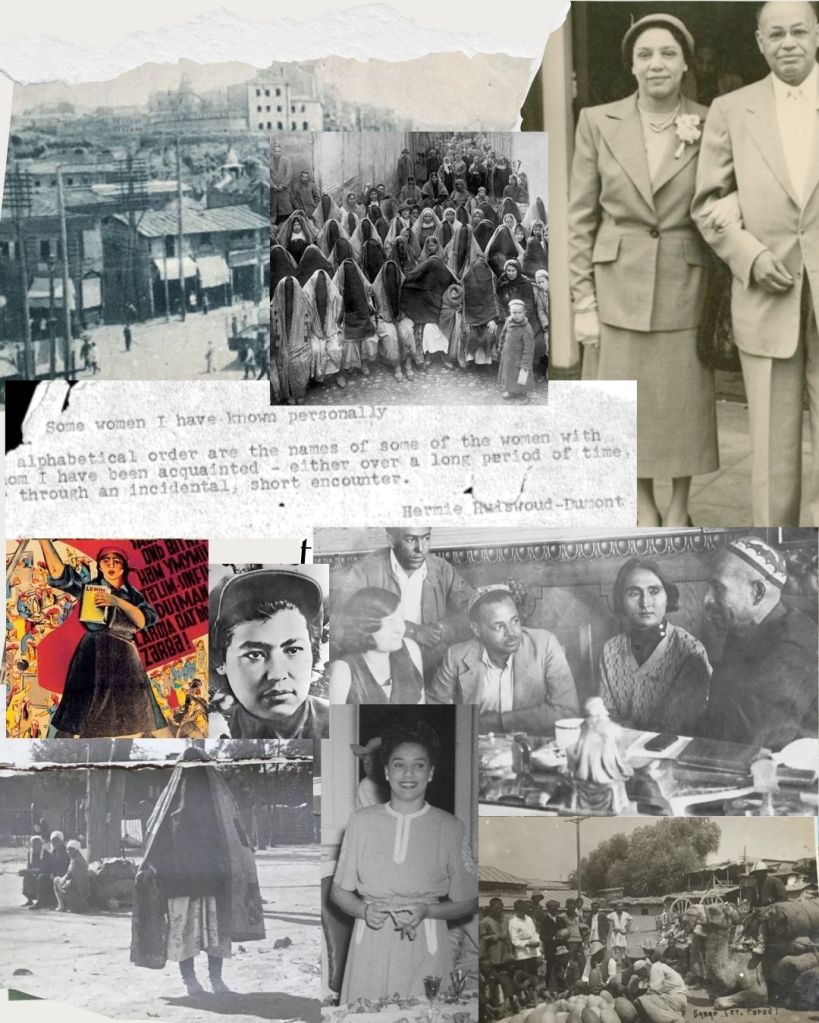

Hermina Dumont Huiswoud (1905–1998) rarely spoke about herself directly. Born in British Guiana, she migrated to Harlem as a teenager during the Great Migration, where she was shaped by a world alive with political thought and artistic ferment.3 She joined organizations like the American Negro Labor Congress and the Harlem Tenants League, worked alongside figures such as Claudia Jones, Grace Campbell, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and married the Surinamese-born communist Otto Huiswoud.4

In Harlem’s charged atmosphere – equal parts arts, Marxism, and dreams of liberation – Huiswoud began to see Black freedom not as a national struggle but as part of a global fight against empire and capitalism.5 When she traveled to the Soviet Union in the early 1930s to study at the Lenin School, she joined a small but significant cohort of Black radicals – Langston Hughes, Louise Thompson Patterson, Williana Burroughs – who sought in Moscow the promise of a world remade.6

But unlike her male counterparts, Huiswoud’s archive doesn’t overflow with letters or manifestos. Instead, she wrote “Women I Have Known Personally,” a collection of biographical sketches of women she encountered in revolutionary movements. In these essays, she told her own story by way of others’: through the translators, domestic workers, and comrades whose lives brushed against hers in fleeting, everyday encounters. So it seems that her preservation of the postcard was a way to record encounters and aspirations, but it also reflected her political commitments – an investment not in self-promotion, but in the networks and solidarities that sustained collective struggle.

The Postcard and the Veiled Woman

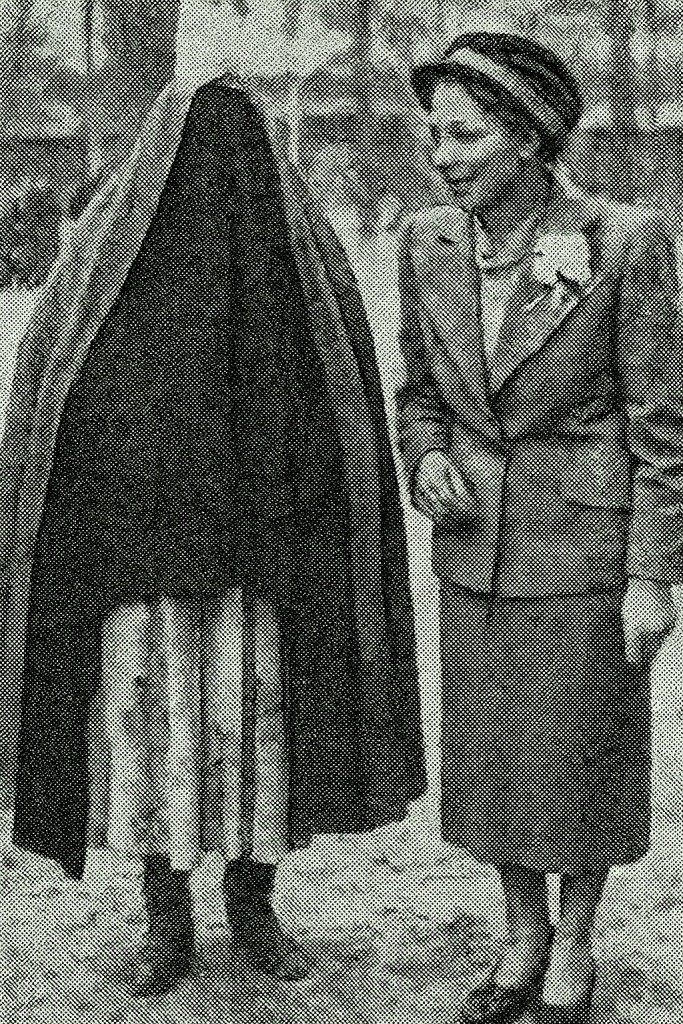

Among the traces she left is that postcard. The photograph, taken somewhere in Soviet Central Asia, shows a veiled woman in the foreground and a cluster of figures sitting or resting behind her, perhaps at a market or a train station. The photographer is anonymous. The moment captured is ambiguous: the community caught mid-motion, the gaze of the woman unreadable.

In its ambiguity lies its power.

At the time the photograph was taken, Soviet photographers were busily documenting the “new” East – the empire’s modernization campaigns in the Muslim-majority republics of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan.7 The veil, in Soviet visual culture, was a potent symbol: a mark of supposed backwardness to be lifted in the name of progress. To unveil was to emancipate. But the state’s rhetoric of liberation often masked violence and domination; “emancipation” was tethered to imperial control.8

For Black radicals visiting the Soviet Union, this tension was not always visible. Many –including Hughes and Huiswoud – were inspired by the Soviet Union’s public stance against racism and colonialism. Yet the very image of the “veiled woman” also carried orientalist undertones, echoing the racialized scripts of Western modernity.9

Was Huiswoud enchanted by this image, or troubled by it? Did she see in the veiled woman* a reflection of her own search for freedom across empire? Or was the postcard simply one of many ephemera passed between travelers, collected without thought?

We cannot know for certain. But that uncertainty is precisely what makes the artifact haunting.

Haunting as Method

Scholar Avery Gordon defines “haunting” as a way of engaging with what is missing yet still felt – with the ghostly presence of histories that refuse to disappear.10 The fractured postcard haunts the archive in this sense: it gestures toward a connection that never happened, a solidarity that could have been.

Perhaps Huiswoud saw in the veiled woman* an echo of her own dislocation – a woman of color navigating an empire, both visible and invisible, desired and surveilled. In the Soviet Union, Huiswoud’s movements were tightly managed by the state. Foreign visitors, particularly from the West, were often barred from traveling to Central Asia. Even her husband Otto, along with Langston Hughes, was permitted to visit the region only under official supervision for the ill-fated film project Black and White.

Hermina Huiswoud stayed behind. The postcard may have been her way of imagining the encounter she could not have – an attempt to reach across language barriers, surveillance, and imperial distance. Perhaps for that very reason, she preserved a small collection of Soviet postcards, among which I found this one. In this reading, the postcard becomes more than just an image: it functions as a medium of desire, a fragile bridge between separated worlds, and a relic of imagined solidarity.

Fracture as Meaning

The physical crease that splits the postcard in two also carries meaning. Was it folded in transit? Damaged in storage? Or was it an unintentional testament to a life of constant movement –packed and unpacked, carried across continents, stored and forgotten, rediscovered decades later?

The fracture may symbolize the tensions within solidarity itself. Huiswoud’s life was defined by connection and disconnection: she reached across racial and political divides but also experienced isolation – first as a Black woman in radical circles dominated by men, later as a communist during the Cold War, when state surveillance shadowed her every move.

The cracked image, then, mirrors the incomplete archive of her life. It invites us to see the gaps not as absences to be filled but as sites of resistance – refusals to be made transparent, to be easily read.

The Women She Met—and the Ones She Couldn’t

In “Women I Have Known Personally,” Huiswoud documented women whose names rarely appear in history books.11 There was Shura, a domestic worker in Moscow who reminded her of her mother; Polskaya, a translator; Williana Burroughs, a Black communist who moved her children to the Soviet Union to be educated in a society free of racism; and many others –Dolores Ibárruri, Grace Campbell, Claudia Jones, Shirley Graham Du Bois.

These sketches are not grand political biographies but small acts of care. She describes gestures, habits, shared meals – quotidian details that resist the monumental narratives of revolution. Through these fragments, we glimpse how solidarity was lived: in the dining halls, dormitories, and train stations of Moscow; in the brief warmth of a stranger’s kindness.

One of her most vivid recollections is of missing a train in Tbilisi and being invited by a local woman to sleep on a bench inside the station. The two women shared space “foot to foot,” rising together at dawn to watch the city awaken before going their separate ways. The encounter is fleeting, tender, and mysterious. Huiswoud doesn’t record the woman’s name or the words they exchanged – perhaps they shared no common language. But the story lingers as a moment of unspoken connection, a glimpse of solidarity made through the body rather than ideology.

Imagined Solidarities

Reading Huiswoud’s archive today means confronting its gaps and silences. It also means allowing imagination to do historical work.

What might it mean to think of solidarity not only as alliance but as haunting – as the persistence of a desire to connect even when communication fails? The postcard of the veiled woman*, cracked and silent, stands as a metaphor for these unfulfilled desires.

The historian cannot reconstruct the exact moment the photo was taken or the reason Huiswoud kept it. But we can use it as a portal to think otherwise: about the ways Black radical women imagined connection across imperial difference, about how archives preserve traces of longing as much as evidence.

In this sense, the postcard invites us to see the archive as a space not just of recovery but of creative speculation. The postcard is not a relic to be decoded but a provocation – a call to think about what solidarities were possible, and what remains possible now.

The Archive Revisited

To revisit an archive is to accept its incompleteness. It means recognizing that some histories –especially those of women of color and radical practices – survive not in full narratives but in the debris: a torn photograph, a line in a notebook, a remembered gesture.

Huiswoud’s fractured postcard resists the state’s desire for order and clarity. It refuses to be a neat document of progress or failure. Instead, it insists on opacity, on what Édouard Glissant called the right to not be understood completely.12

In this sense, the postcard aligns with the ethos of The Archive Revisited: to return to the fragments not to fix them, but to listen differently. The veiled woman*, the ghostly companion of Huiswoud’s archive, demands that we stay with the uncertainty, that we imagine solidarities that were missed or misread.

Why This Story Matters Now

In our moment – marked by resurgent authoritarianism, the policing of borders, and the commodification of identity – the story of Hermina Dumont Huiswoud and her haunting postcard feels newly urgent. It reminds us that solidarity has always been fraught, partial, and precarious. Yet it also reminds us that the desire to connect across difference – to see oneself in the struggle of others – is itself a radical act.

Huiswoud’s disappointment at the collapse of the Soviet Union, recorded late in her life, was not nostalgia for empire but for a lost dream of global solidarity.13 The postcard, in its silence, holds that dream: a longing for a world where the struggles of Black and Indigenous, colonized and working-class women might converge – not in sameness, but in shared refusal.

Conclusion: Listening to the Ghosts

The fractured postcard of the veiled woman* is not just a historical object. It’s a message from the margins, asking us to attend to what remains unspoken in our own archives – personal, political, collective.

It asks: What solidarities have we missed? What encounters have been silenced? And how might we, in revisiting the archive, learn to listen to the ghosts who still insist on being heard?

For Hermina Dumont Huiswoud, who told her story through the stories of others, the postcard may have been a quiet act of resistance – an acknowledgment that some connections can only exist in imagination. Yet imagination, as this haunting artifact shows us, is also where the work of solidarity begins.

This blog post is based on the article “Haunting Encounters: Reimagining Hermina Dumont Huiswoud’s Trip to the Soviet Union, 1930–1933” by Tatsiana Shchurko (2024), published in Red Migrations: Transnational Mobility and Leftist Culture After 1917, edited by Bradley Gorski and Philip Gleissner, pp. 398–428. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/jj.22992804.18.

Notes

I use an asterisk to trouble my assumption that the person on the photo postcard is a woman. In colonial consciousness, the veil serves as a common trope that enables subject formation through discourse that produces and homogenizes racialized femininity. At the same time, for oppressed communities, the veil may appear as an important site for political resistance against Western racial/sexual logic while not denying the suppressing role it may play in anti-colonial national narratives. Therefore, in this chapter, an asterisk is used to acknowledge the multiplicity and heterogeneity of bodies, expressions, identities, meanings, and positionalities that may stay behind the loaded image of the veiled figure and go beyond the imposed gender binary.

2 The postcard is located in box 1, folder 30 HDHP; TAM 354; Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University Libraries.

3 Joyce Moore Turner, Caribbean Crusaders and the Harlem Renaissance (University of Illinois Press, 2005), 5.

4 Turner, Caribbean Crusaders, 7, 136, 154.

5 Hermie Dumont, “Notes on the West Indies,” The Liberator 1, no. 48 (15 March 1930): 3.

6 Turner, Caribbean Crusaders, 187.

7 The photo postcard as a genre was invented at the turn of the twentieth century, and, like photography more generally, became a vital tool in the production of ethnographic knowledge and constructions of the “other.” Thus, in the 1840s, Sergei Levitsky, a pioneering photographer in the Russian empire, conducted his first experiments with daguerreotype photography, making images of the Caucasus. Russian imperial photography was in line with trends in other Western empires, representing Russia as a modern European power with a civilizing mission directed towards indigenous communities. After 1898, in the Russian Empire, more than 1,000 postcards with images of Central Asia were published. See Ali Behdad and Luke Gartlan, eds., Photography’s Orientalism (Getty Research Institute, 2013); Inessa Koutienikova, “The Colonial Photography of Central Asia (1865-1923),” in Dal Paleolitico al Genocidio Armeno Ricerche su Caucaso e Asia Centralea cura di Aldo Ferrari, Erica laniro (Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, 2015), 85-108; and David Prochaska and Jordana Mendelson, eds., Postcards: Ephemeral Histories of Modernity (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010).

8 For similar critique, see Alastair Bonnett, “Communists Like Us: Ethnicized Modernity and the Idea of ‘the West’ in the Soviet Union,” Ethnicities 2, no. 4 (2002): 435-67; Adrienne Edgar, “Emancipation of the Unveiled: Turkmen Women under Soviet Rule, 1924-29,” Russian Review 62, no. 1 (2003): 132-49; Douglas Northrop, Veiled Empire (Cornell University Press, 2004); Marianne Kamp, The New Woman in Uzbekistan (University of Washington Press, 2006); Adeeb Khalid, “Backwardness and the Quest for Civilization,” Slavic Review 65, no. 2 (2006): 231-51; Stephanie Cronin, Anti-Veiling Campaigns in the Muslim World (Routledge, 2014); Madina Tostanova, “Why the Postsocialist Cannot Speak: on Caucasian Blacks, Imperial Difference, and Decolonial Horizons,” in Postcoloniality-Decoloniality-Black Critique, ed. Sabine Broeck and Carsten Junker (Campus Verlag, 2015), 159-74; Mohira Suyarkulova, “Fashioning the Nation: Gender and Politics of Dress in Contemporary Kyrgyzstan,” Nationalities Papers 44, no. 2 (2016): 247-65.

9 Erik S. McDuffie, Sojourning for Freedom (Duke University Press, 2011), 72.

10 Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

11 WBE, n.d., box 1, folder 35, HDHP.

12 Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (The University of Michigan Press, 1997).

13 Turner, Caribbean Crusaders, ix-x.